Thoughts

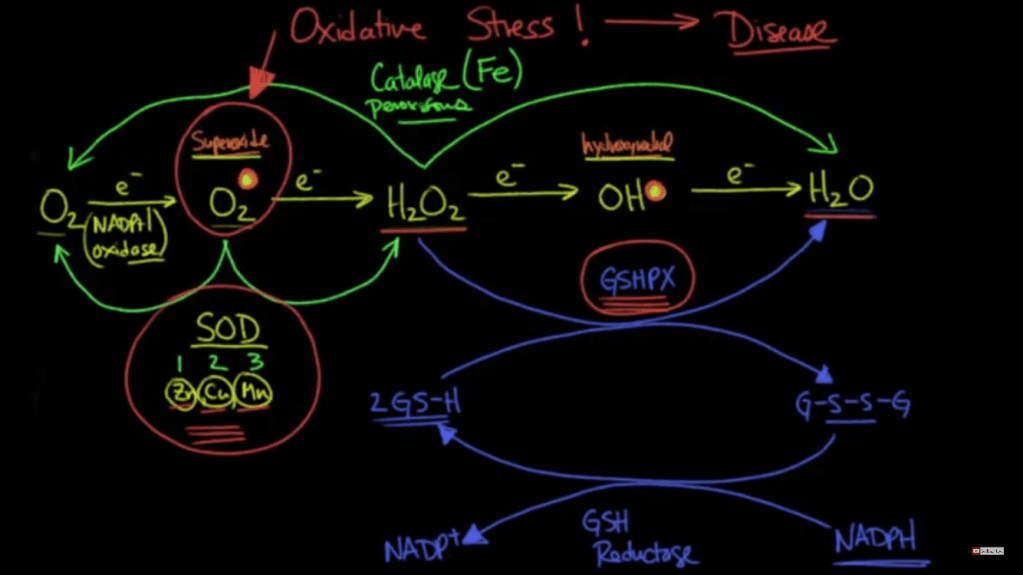

My previous post discussed how Fe+2 could theoretically enter through something like a VGCC because of its same size and charge as Ca+2. I see this being a possibility in a deficient state where the body is unable to make tf, DMT1, and Frataxin. Or you have ROS/RNS or some other mechanism that damages these chaperones. In this situation you probably have reduced glutathione from a down regulation of the sulfation cycle which means the mitochondria and cell are prime for Fenton reactions. Also, GSH is needed to chaperone Cu+2 intracellularly which would add to the damage.

At this point does it really matter if it’s the Ca+2 or Fe+2 (etc.) causing the membrane permeability transition pore? The mitochondria, then cell, will die regardless. In a cancer cell this would be desired so I wonder if there is a way to leverage a situation like this? The problem seems to be like the glaring issue with chemotherapy, you would damage your healthy cells too. Fixing the higher order cause from deficiencies seems to be the more pertinent issue. We need SOD, GSH, catalase peroxidase, etc.

It is true that a Fe (and Cu) pool that becomes impossible to manage from people continually consuming foods high in these would cause a chaperone deficiency too. So it’s important to get things back in circulation.

Figures

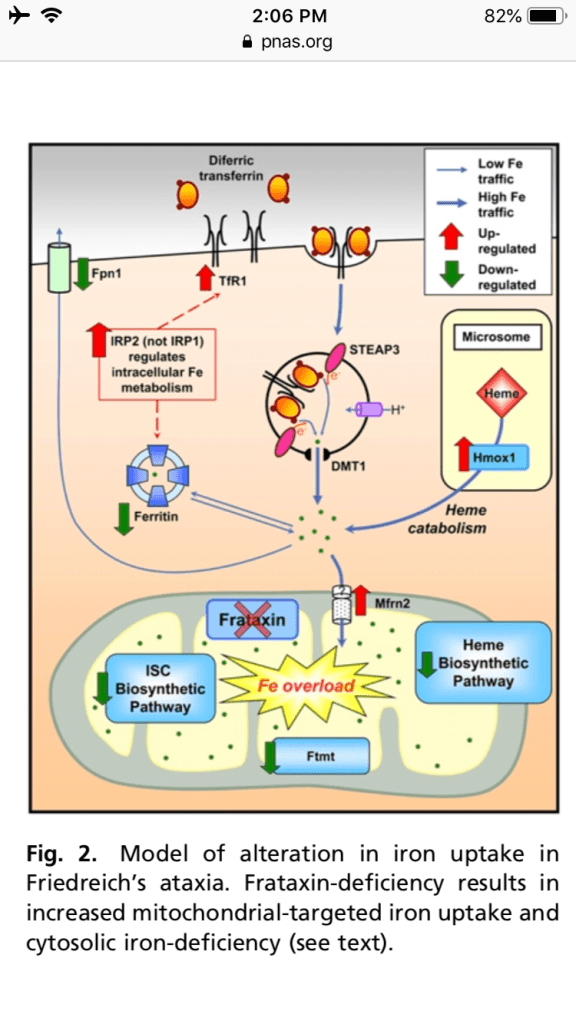

Because of its redox properties, iron can catalyze the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can be highly toxic (3). Therefore, under normal physiological conditions, iron is specifically transported in the blood by diferric transferrin (Tf) (4, 5). All tissues acquire iron by the binding of Tf to the transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1), with this complex then being in- ternalized by receptor-mediated endocy- tosis (4, 5) (Fig. 1A). Recent studies have demonstrated that the internalization of the Tf-containing endosome via the cyto- skeleton is under control of intracellular iron level

In vitro, iron release from Tf requires a “trap,” such as pyrophos- phate (13), but a physiological chelator serving this role has not been identified. In erythroid cells, once iron(III) is released from Tf in the endosome, it is thought to be reduced to iron(II) by a ferrireductase in the endosomal membrane known as the six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3 (14, 15) (Fig. 1A). After this step, iron(II) is then transported across the endosomal membrane by the divalent metal transporter-1 (DMT1) (16) and forms, as generally believed, the cytosolic low Mr labile or chelatable iron pool (17). This pool of iron is thought to supply the metal for storage in the cytosolic protein ferritin and for metabolic needs, including iron uptake by the mitochondrion for heme and ISC synthesis.

Iron can also be released from the cell by the transporter, ferroportin1 (18) (Fig. 1A). Ferroportin1 expression can be reg- ulated by the hormone of iron metabo- lism, hepcidin. Hepcidin is a key regulator of systemic iron metabolism (18) and is transported in the blood bound to α2- macroglobulin (18). Hepcidin secretion by the liver is stimulated by high iron levels and also inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (19).

Once iron is trans- ported out of the endosome via DMT1 {divalent metal transporter 1}, it enters the chelatable or labile iron pool (Fig. 1A) that traditionally was thought to consist of low Mr complexes (e.g., iron-citrate) (17, 25, 26). The only strong evidence that such a pool exists comes from studies with che- lators that mobilize iron from cells (27, 28). However, it is just as likely that these com- pounds remove iron from organelles and proteins as it is that they chelate iron from genuine cytosolic low Mr complexes

Mitoferrin-1 is localized on the inner mitochondrial membrane and func- tions as an essential importer of iron for mitochondrial heme and ISC in erythro- blasts and is necessary for erythropoiesis (60). Mitoferrin-1 is highly expressed in erythroid cells and in low levels in other tissues, whereas mitoferrin-2 is ubiqui- tously expressed (61). The half-life of mitoferrin-1 (but not mitoferrin-2) in- creases in developing erythroid cells and this may be part of a regulatory mecha- nism aiding mitochondrial iron uptake

“kiss and run” hypothesis (11) (Fig. 1B). This model suggests that a direct transfer of iron from the Tf-containing endosome to the mitochondrion occurs, by-passing the cytosol

con- ditional frataxin-deletion in cardiomyocytes leads to depressed ISC and heme synthesis, mitochondrial iron-loading, TfR1 up-regu- lation, and thus increased iron uptake from Tf.

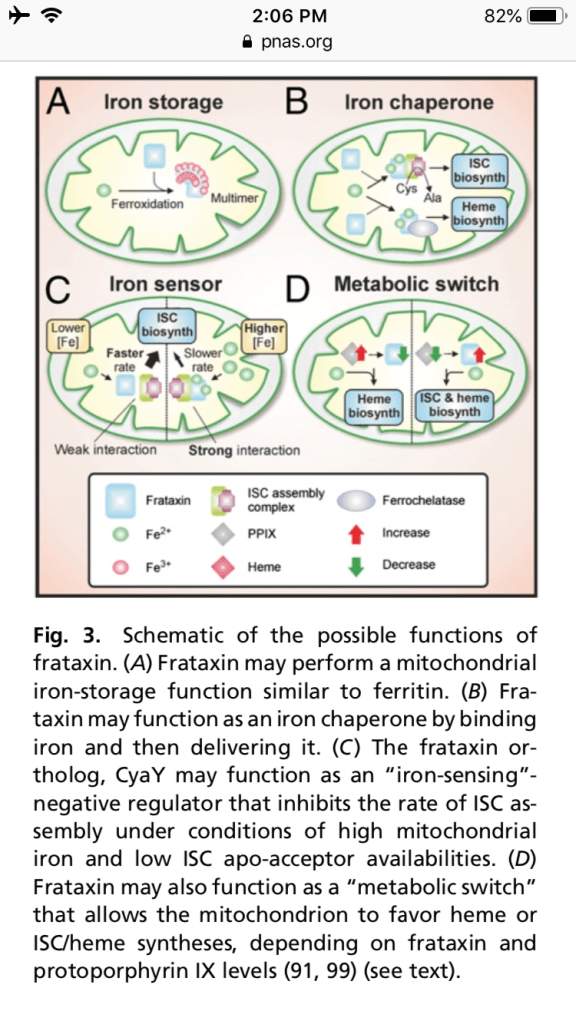

Frataxin has been proposed to function as a mitochondrial iron storage protein. Perhaps the most promising emerging role for frataxin is as an iron chaperone (Fig. 3B) for ISC and heme biosyntheses. Frataxin has been ob- served to interact with, and presumably donate iron to, iron-dependent proteins involved in ISC and heme biosyntheses.

may act as an “iron-sensor” (Fig. 3C) that negatively regulates the rate of ISC biosynthesis under conditions of high iron and low ISC apo-acceptor availabilities (89). If we extend this model to eukaryotic systems, a deficiency in fra- taxin expression is presumably deleteri- ous because the rate of ISC biosynthesis may exceed the availability of ISC apo- acceptors, resulting in the overproduction of ISCs that are unstable in an unbound form (89). Essentially, this model suggests that over and above functioning as an iron donor in ISC biosynthesis, frataxin may exert “kinetic control” over the rate of ISC biosynthesis, depending on the rela- tive availabilities of iron and ISC apo- acceptor

frataxin ex- pression is markedly decreased during Friend cell hemoglobinization (99), it

is possible that frataxin may be down- regulated during erythroid differentiation to allow higher rates of heme synthesis, potentially at the expense of decreased levels of ISC synthesis

Notes

Iron is needed not only for heme and iron sulfur cluster (ISC)-containing proteins involved in electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation, but also for a wide variety of cytoplasmic and nuclear functions, including DNA synthesis. the discovery of proteins involved in mitochondrial iron storage (mitochondrial ferritin) and transport (mitoferrin-1 and -2). In addition, recent work examining mitochondrial diseases (e.g., Friedreich’s ataxia) has established that communication exists between iron metabolism in the mitochondrion and the cytosol. This finding has revealed the ability of the mitochondrion to modulate whole-cell iron- processing to satisfy its own requirements for the crucial processes of heme and ISC synthesis. Knowledge of mitochondrial iron- processing pathways and the interaction between organelles and the cytosol could revolutionize the investigation of iron metabolism.

the mitochondrion is the sole site of heme synthesis and a major generator of ISCs, both of which are present in mitochondria and cytosol. Iron is an essential metal for the organism because of its unparalleled versatility as

a biological catalyst. Consequently, iron is a crucial element required for growth. However, the very chemical properties of iron that allow this versatility also create a paradoxical situation, making acquisition by the organism very difficult. Indeed, at pH 7.4 and physiological oxygen tension, the relatively soluble iron(II) is readily oxidized to iron(III), which upon hydrolysis forms insoluble ferric hydroxides. As a result of this virtual insolubility and po- tential toxicity because of redox activity, iron must be constantly chaperoned.

Still unknown how Fe crosses the outer mitochondria membrane.

Once iron is trans- ported into the mitochondrion it can then be used for heme synthesis, ISC synthesis, or stored in Ftmt. It is essential that mi- tochondrial iron is maintained in a safe form to prevent oxidative damage, as mi- tochondria are a major source of cytotoxic ROS (3). Hence, it is likely that as in the cytosol, iron is carefully transported within the mitochondrion in a form distal to the aqueous environment, deep in the hydro- phobic pockets of communicating proteins that form iron transport pathways.

Like a typical ferritin, Ftmt shows ferrox- idase activity and binds iron (66). Ftmt was found at the highest lev- els in the testes and the erythroblasts of sideroblastic anemia patients (67, 68). Mi- tochondrial ferritin has also been detected in the heart, brain, spinal cord, kidney, and pancreas (67). Unlike cytosolic ferritin, Ftmt is not highly expressed in the liver and spleen, suggesting that it plays a distinct role. These findings led to the hypothesis that Ftmt plays a role in protection from iron-dependent oxidative damage.

Being a major site of ISC assembly, the mitochondrion plays a pivotal role in the biosynthesis of ISC proteins (1, 2). ISCs consist of iron and sulfide anions (S2-), which assemble to form [2Fe-2S] or [4Fe-4S] clusters (2). These clusters form cofactors in proteins that perform vital functions, such as elec- tron transport, redox reactions, metabolic catalysis, and other such functions (70). In eukaryotic cells, more than 20 mole- cules facilitate maturation of ISC proteins in the mitochondria, cytosol, and nucleus (2). Functional defects in ISC proteins

or components involved in their biogenesis lead to human diseases (71, 72). Bio- synthesis of ISCs and their insertion into apo-proteins requires both the mitochon- drial and cytosolic machinery.

The mitochondrion contributes a yet-to-be discovered compound necessary for the biogenesis of ISCs outside of this com- partment [mitochondrial ISC assembly system] I.e., in the cytosol or other or- ganelles).

The third major mito- chondrial metabolic pathway that utilizes iron is that of heme synthesis that is ex- clusive to this organelle.

Apart from importing iron, the mitochondrion synthe- sizes heme and ISCs that subsequently are transported out to the cytosol. These export processes are important to understand, as decreased release of iron as heme or ISCs —or their precursors—can contribute to mitochondrial iron-loading.

It is unknown how heme is exported from the mitochondrion. However, its low solubility and highly toxic nature suggest an efficient heme-carrier must be involved. Considering this, heme-binding protein 1 has been identified as a candidate for this carrier (83). The expression of this mole- cule is ubiquitous, but it is also increased during erythroid differentiation and high levels are found in the liver (83). Heme- binding protein 1 binds one heme per mole of protein (83) and, although it could be a candidate for heme transport, direct evidence for this is lacking.