Paper

vitamin K plus C as a powerful redox-system, which forms a bypass between mitochondrial complexes II and III and thus prevents mitochondrial dysfunction, restores oxidative phosphorylation and aerobic glycolysis, modulates the redox-state of endogenous redox-pairs, eliminates the hypoxic environment of cancer cells and induces cell death. The analyzed data suggest that vitamin C&K can sensitize cancer cells to conventional chemotherapy, which allows achievement of a lower effective dose of the drug and minimizing the harmful side-effects.

developed large subcutaneous and intramuscular hemor- rhages. Henrik Dam has designated this factor as “Koagulation vitamin” (from Danish) or vitamin K in short, because of its vital role for normal haemostasis

Initial experiments with additions of lemon juice, cholesterol, cod-liver oil or ascorbic acid to the diet failed to prevent hemorrhages [1–3]. Later it has been discovered that vitamin K is an essential cofactor for post-translational modification of hepatic blood- coagulating proteins (as prothrombin, factors II, VII, IX and X) [3,4]. Vitamin K participates in the converting of their glutamic acid residues into γ-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla) residues.

role in bone metabolism, vascular calcification, regulation of cell growth and apoptosis

Vitamin K is a group of structurally related molecules that have a 2- methyl-1,4 naphthoquinone ring and a variable aliphatic chain (Fig. 1A). The variable aliphatic chain distinguishes two naturally oc- curring forms: vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) and vitamin K2 (menaqui- none). There is also a synthetic form of vitamin K without aliphatic chain (K3 or menadione), which is classified as a pro-vitamin. Vitamin K1 exists only in one phylloquinone structure, while vitamin K2 exists in multiple structures, which are distinguished by number of un-

saturated isoprenyl groups in the aliphatic chain [10].

Vitamin K1 is found in green leafy vegetables: broccoli, lettuce, spinach, fermented soy (natto), spring onions, cabbage, etc. The various forms of vitamin K2 (MK-4, MK-7, MK-10) are mainly synthesized by bacteria, especially in nutrient products as natto and yogurt [11,12].

Vitamin K2 is also found in meat, eggs, curd and cheese [7,10,13]. Vitamins K1 and K2 are transported by triglyceride-rich lipoprotein (TGRLP) to the liver, after intestinal absorption [13,14] (Fig. 1B). Vi- tamin K1 is metabolized and more than half the amount is excreted by the organism, while vitamin K2 is transported from the low density

lipoproteins (LDL) to extra-liver tissues [13,14]. Vitamin K2 is accu- mulated preferentially in peripheral tissues. High levels are detected in the brain, aorta, pancreas, fat and low levels are detected in the liver [15–17].

Pro-vitamin K3 is a synthetic lipid-soluble vitamin precursor, which can be converted to active vitamin K2 (menaquinone) after its alkyla- tion in the liver. In addition, pro-vitamin K3 could be metabolized to glucuronide and sulfate of reduced menadione, which are excreted in the urine [18–20]. Menadione has a relatively low toxicity and is ap- proved by the Food and Drug Administration for therapeutic purposes. It has been shown that pro-vitamin K3 directly affects the redox status of thiols (including thiol-containing compounds) and calcium home- ostasis [20]. The most intriguing property of menadione is its antic- ancer activity

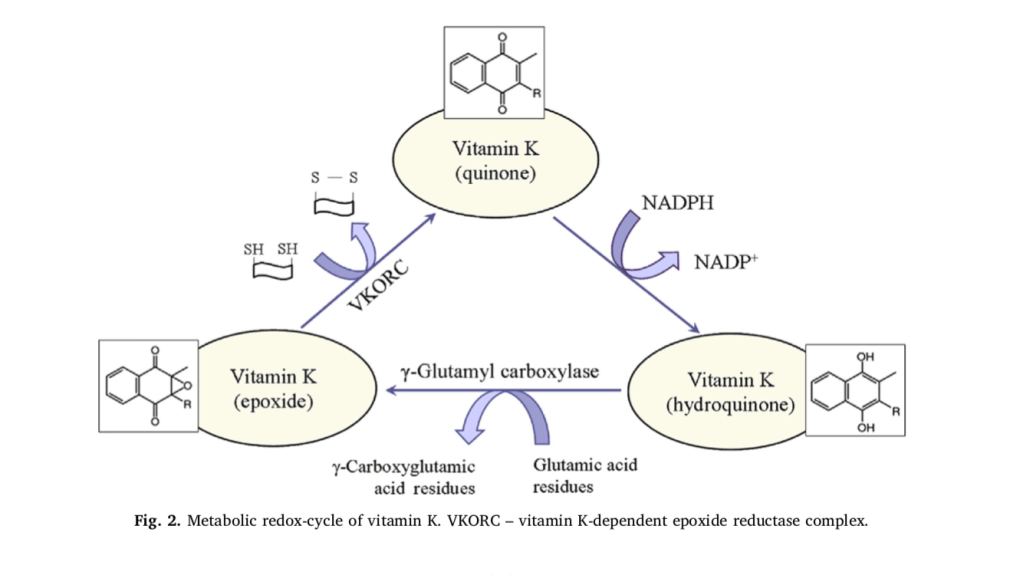

It is generally accepted that the essential role of vitamin K is related to the post-translational γ-carboxylation of glutamate residues of pro- teins (Fig. 2). This process occurs in the lumen of the endoplasmic re- ticulum and involves two enzymes: γ-glutamyl carboxylase and vitamin K-dependent epoxide reductase complex (VKORC). Both enzymes to- gether constitute the “vitamin K cycle”, which is a redox-cycle in its biochemical essence [21,22]. In nature, vitamin K exists in an oxidized form (quinone), but γ-carboxylation of glutamate residues requires its reduced form (hydroquinone). In the organism, quinone is reduced to hydroquinone by NAD(P)H and/or glutathione (GSH). In turn, hydro- quinone is converted to epoxide in the process of γ-carboxylation. The epoxide is converted to the initial oxidized quinone state by the VKORC, which is accompanied by a consumption of other reducing equivalents (mainly thiol-groups). Obviously, the activity of vitamin K may affect redox-homeostasis of cells and tissues and can be considered as a regulatory factor in redox-signaling. This function of vitamin K is very important due to variety of glutamic acid-rich proteins in the bones, arteries and soft tissues. For example, vitamin K influences the degree of carboxylation of osteocalcin – a small calcium-binding pro- tein, which is secreted by osteoblasts in bones and serves as an integral protein for the synthesis of bone matrix [23–25]. The biosynthesis of osteocalcin is regulated by hormones and growth factors, but its post- translational modification is regulated by vitamin K. Osteocalcin con- tains three Gla residues, which interact with calcium in the hydro- xyapatite-crystal lattice of bones [24]. γ-Carboxylation of glutamic acid residues of osteocalcin increases its affinity to calcium and respectively to hydroxyapatite [25]. It was shown, that decarboxylated osteocalcin cannot bind calcium, which emphasizes the essential role of vitamin K in the γ-carboxylation process [26,27]. In addition, vitamin K inhibits the activity of osteoclasts, thus preventing the breakdown of bones [27,28].

Vitamin K participates in the carboxylation of the matrix Gla-con- taining protein (MGP) of the arterial walls and plays a crucial role in maintaining their elasticity [7,8,29,30]. MGP belongs to the group of vitamin K2-dependent Gla-containing proteins. MGP is produced in bones and vascular smooth muscle cells and inhibits vascular calcifi- cation [30–32]. Its function is affected by inflammatory factors [32]. The importance of MGP for vascular homeostasis was demonstrated on MGP-deficient animals – all of them died of massive arterial calcifica- tion within 6–8 weeks after birth [5,33]. It was established that non- carboxylated MGP forms calcium depositions in the vascular walls [8,27,34]. The calcium phosphate crystals in the arterial wall directly attract macrophages and induce inflammation [27,35,36]. Studies have demonstrated that rats with vitamin K-deficiency and chronic kidney disease have an enhanced vascular calcification, which decreases after vitamin K supplementation [31,37]. Warfarin, an inhibitor of vitamin K reduction, affects γ-glutamyl carboxylation of MGP and induces vas- cular calcification in experimental animals [4,31,34,38]. The effect is abolished by vitamin K treatment [4,31,38]. These findings suggest that vitamin K-deficiency affects calcium homeostasis, which leads to vas- cular calcification and bone disorders.

Quinones can undergo one-electron reduction, producing inter- mediate semiquinone radicals, as well as two-electron reduction with production of hydroquinones (Fig. 3) [41]. Both reactions are accom- panied by consumption of superoxide radicals and reducing equivalents (as NADH, NADPH, glutathione), which are essential for cancer cell homeostasis [42,43]. It is generally accepted that superoxide is “on- cogenic ROS”, while hydrogen peroxide is “onco-suppressive ROS” [43–46]. Numerous studies suggest that cellular state, where the ratio tilts predominantly in favor of superoxide, inhibits apoptosis and pro- motes cell survival. If the ratio tilts in favor of hydrogen peroxide, this creates an intracellular environment suitable for induction of apoptosis and cell death.

this context, the decrease of superoxide due to vitamin K redox-cycle may explain, at least partially, its anticancer activity. On the other hand, semiquinone radical of vitamin K can convert transition metal ions, e.g. Fe3+ to Fe2+, thus inducing Fenton’s reactions and production of highly reactive and cytotoxic hydroxyl and hydroperoxyl radicals [10,49].

It is shown that pro-vitamin K3 induces oxidative stress in cancer cells via production of hydroxyl radicals and DNA strand-breaks.

Superoxide dismutase does not influence the anticancer effect of menadione [52,53]. However, antioxidant enzymes, involved in the depletion of “onco-suppressive” hydrogen peroxide (as catalase and glutathione peroxidase), decrease the anticancer effect of menadione [53,54]. Similar data have also been reported for transition metal chelators that suppress Fenton’s reactions and menadione-mediated cytotoxicity in cancer [55]. The described data suggest that pro-vitamin K3 leads to depletion of “oncogenic” superoxide and probably induces apoptosis via production of “onco-suppressive” hydroperoxides and cytotoxic hydroxyl radicals. This explains, at least partially, the antic- ancer activity of menadione. However, it should be noted that the in- duction of Fenton’s reactions and the production of hydroxyl radicals suggest for potential side-effects (cytotoxicity) of menadione on normal cells.

Other studies suggest that vitamin K induces apoptosis through different biochemical pathways, including alteration of intracellular calcium homeostasis and activation of the following pro-apoptotic factors: c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), Fas-dependent and Fas-in- dependent pathways, and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) [56–61].

Most of the vitamin K-induced pro- apoptotic factors are inflammatory signals, inducing overproduction of ROS (mainly hydroperoxides) and oxidative stress in cancer cells and tissues [43,48]. The data also suggest that vitamin K decreases the le- vels of superoxide, NAD(P)H and glutathione, which are essential for hypoxic behavior of cancer cells and their homeostasis.

glucose meta- bolism is a unique pathway. It can utilize oxygen if available (aerobic pathway – via conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA) or it can function in the absence of oxygen (anaerobic pathway – via conversion of pyr- uvate to lactate). Both pathways are necessary for the functioning of cells, tissues and organs, but in norm, the aerobic pathway dominates the anaerobic. In cancer cells, the anaerobic oxidation of glucose is a major source of energy. In many cancers, the major cause of anaerobic glycolysis is mitochondrial dysfunction and inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation. Cancer cells are characterized by high levels of glu- cose, anaerobic oxidation of glucose (Warburg effect) and accumulation of lactate, compared to normal cells [43,44,48,79]. In last years, lactate dehydrogenase is receiving a great deal of attention as a potential di- agnostic marker or a predictive biomarker for many types of cancer and as a therapeutic target for development of new anticancer drugs [80–82].

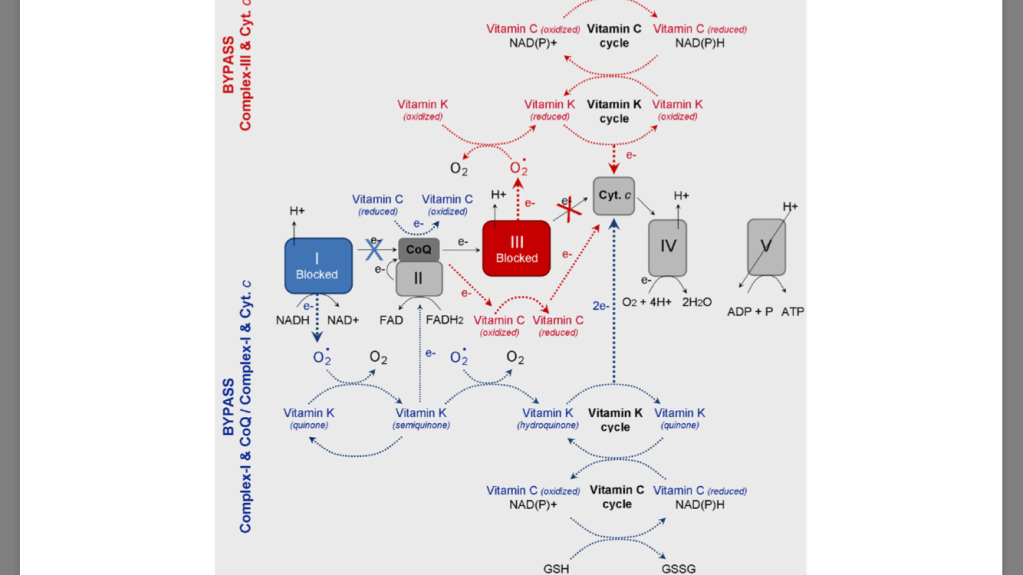

severe defect in complex III of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (mitochon- drial dysfunction). Deficiency of reducible cytochrome b (cyt. b), which is accompanied by an effec- tive prevention of aerobic metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation. The authors bypass the deficient complex III by using pro-vitamin K3 and vitamin C as electron transfer mediators to carry the electrons from coenzyme Q (CoQ) to cyt. c. Thus, they succeeded to increase ATP production rate to about 65% of the normal state in mitochondria, as well as to decrease the lactic acidosis in the patient. The combination of vitamin C and K3 results in a production of more ATP, than in the case of vitamin C applied alone. The authors suggest that both vitamins can reduce directly cyt. c, since the reduction potential of cyt. c is over + 200 mV – more positive than those of menadione or ascorbate.

treatment of cells with vi- tamin C and K3 results in spikes in ATP production due to a shunt around a defective area of complex III of the mitochondrial electron- transport chain (between CoQ and cyt. c) [74,75,88–91]. This reaction causes a shift from anaerobic (glycolytic) to aerobic (oxidative) meta- bolism, which diminishes hypoxia and lactic acidosis.

case of dysfunc- tion in Complex-III (due to mutations in cyt. b), the electrons can not be transferred from CoQ to cyt. c. In the case of dysfunction in Complex-I (due to mutations in NADH dehydrogenase), the electrons are blocked on the first step of respiratory chain. It is well-known that both types of mutations are accompanied by superoxide production from complex-III and complex-I and suppression of ATP synthesis [43,48]. The oxidized vitamin K (KQ) can accept electrons from superoxide, converting con- sequently to semiquinone (KQH•) and hydroquinone (KQH2). Finally, the reduced vitamin K can transfer electrons directly to cyt. c. the oxidized vitamin C (dehydoroascorbate) can accept electrons di- rectly from Complex-I (NADH) or CoQ, converting consequently to semidehydroascorbate (Asc•) and ascorbate (Asc). Finally, the reduced vitamin C can transfer electrons to cyt. c. The two redox-cycles lead to a bypass between Complex-I (or Complex-III) and cyt. c. This will restore the oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis. ATP, generated due to the vitamin C&K-mediated bypasses, prevents the anaerobic condi- tions, decreases the levels of “oncogenic” superoxide, decreases the levels of lactate, eliminates the lactic acidosis and hypoxia, and allows the cancer cells to trigger autophagia and “to kill themselves”.

redox cycles of vitamins C and K are cross-linked – ascorbate can reduce pro-vitamin K3, which is accompanied by a production of hydrogen peroxide (“onco-suppres- sive” and cytotoxic ROS) [92,93]. The reduction of vitamin K by vi- tamin C allows also a direct (superoxide-independent) reduction of cyt. c by vitamin K (KQH2). Silvera-Dorta et al. have also reported that vi- tamin C can reduce CoQ and the process is coupled with reduction of oxygen to hydrogen peroxide

The redox-system vitamin C&K3 could also influence the ratio be- tween the oxidized and reduced forms of the main endogenous redox- pairs: NAD+ /NADH, NADP+ /NADPH, GSH/GSSH, etc

The balance between oxidized and reduced forms is crucial for the cell behavior, as well as for cell survival or death. It is widely accepted that the increased mitochondrial oxi- dative stress and high levels of NAD(P)H and glutathione are distinctive features of the metabolic phenotype of cancer cells [43,44,47,48]. Since the reduction potentials of NAD(P)H, FADH2 and GSH are very low (below −200 mV), all substances can directly reduce vitamins C and K.

The redox-cycles of vitamins C and K are cross-linked and both vi- tamins can serve as associated redox-modulators (a redox-shuttle). The combination vitamin C&K can serve as a bypass between complex I (or complex-III) and cyt. c of mitochondrial respiratory chain and to donate electrons (directly or indirectly) to cyt. c, passing from reduced to oxidized form. Both vitamins can be also converted into reduced forms, consuming NAD(P)H and/or GSH. These processes are accompanied by an increase in ATP synthesis and accumulation of high levels of NAD(P) + and GSSH, which restores oxidative phosphorylation and aerobic glycolysis and eliminates the hypoxic environment. Тhe specific beha- vior of the cancer cells is disrupted and apoptosis is initiated. It is as- sumed that changing the ratio NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H and/or GSH/GSSH in cancer cells could be the “switch mechanism” from survival to cell death. Targeting defective mitochondria in cancer cells and preventing their dysfunction, as well as modulating redox-state of endogenous redox-pairs can be a successful strategy for anticancer therapy. This strategy allows target cytotoxicity, which is not directed to normal cells and tissues [43,48].

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213231718300934

Thoughts

I wonder how this would change with the whole vitamin C complex? They mostly looked at the synthetic K3, I wonder what changes with K2? This consumes NAD and GSH so that needs to be addressed. Especially with the comments about the increased possibility of a Fenton reaction. If GSH is needed to transport Fe within the cell then taxing it further could make this more likely.

The part about hydrogen peroxide being onco-suppressive ROS is very interesting. And needing to tip the scale away from superoxide to hydrogen peroxide to stimulate apoptosis is very important. But again this needs reducing equivalents which require raw materials. Dr GRJ says glutathione comes indirectly from methylation. And glutathione reductase OSs FAD (B2) dependent which will fix the altered GSH:GSSG ratio. FAD = quinone, FADH2 = hydroquinone, and FADH = semiquinone. I wonder if FAD can do this too?

By passing complex I and III and seeing an increase in ATP by 65% is hugely important. I think finding more things that help bypass complexes staight to complex IV or the ATPase will be important to help many with low ATP states. Cold thermogenesis is known to stimulate thermogenin (UCP1) which transports protons from the inner mitochondrial space to the matrix, uncoupling the ETC. This occurs in brown adipose tissue. Do want more heat production or more ATP though?

Ling says we need ATP as a cardinal absorbent. “Cardinal adsorbents hold protoplasm in one or another state by a propagated polarization along the length of polypeptide chains. Adsorption or desorption of the cardinal adsorbents may alter the cooperative state of the protein- water-ion system in an “all-or-none” manner”. “proteins adsorbing a solute also polarize water; in this case the cardinal adsorbent controls at once the distribution of adsorbed solute and the free solute dissolved in the water. In nature, perhaps the more frequently observed case is one in which different proteins are involved in solute adsorp- tion and in water polarization”. But you still need the “heat source” for the jello. So maybe the UCP making heat is important.

Then you have Dr Arturo Herrera whose research shows melanin splits the water in the cell making energy. I wonder what frequency of energy? I bet it’s IR so the sunlight provides the heat source during the day and the reason our body temperature drops at night is to stimulate the UCP to allow the mitochondria to release heat (IR). Herrera says the melanin is around the cell nucleus. I wonder if you would be able to see the difference? The heat source coming from one relatively larger nucleus during the day and from many smaller mitochondria at night.